INSTITUTE

INSTITUTE is a visual storytelling company, which serves media, editorial, advertising, entertainment, record industry, fine art, book publishing, online/mobile media and corporate clients.

INSTITUTE operates out of Los Angeles (USA) and Bath (UK).

Want us to distribute your story? Information on submissions can be found here

INSTITUTE

INSTITUTE is a visual storytelling company, which serves media, editorial, advertising, entertainment, record industry, fine art, book publishing, online/mobile media and corporate clients.

INSTITUTE operates out of Los Angeles (USA) and Bath (UK).

Want us to distribute your story? Information on submissions can be found here

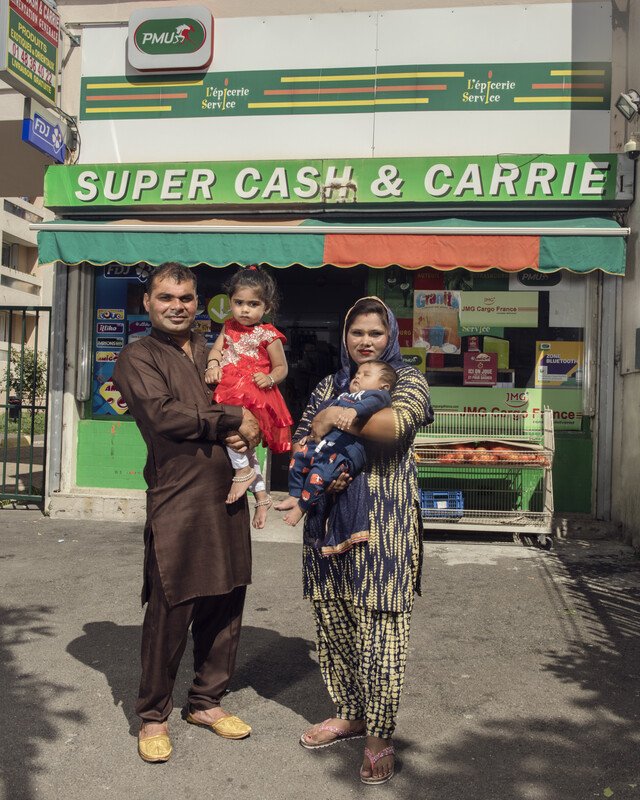

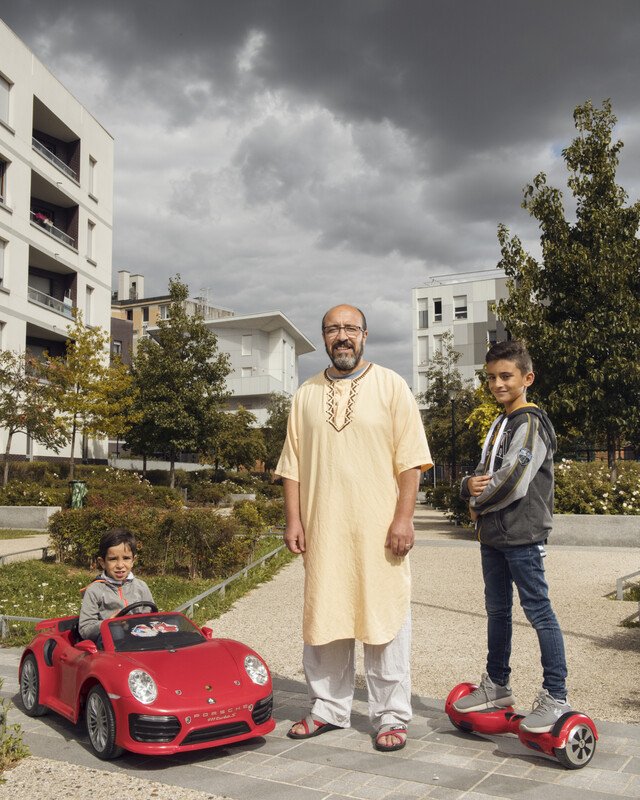

93, Terre de Mixité

© Stephan Gladieu

93, Terre de Mixité

© Stephan Gladieu

The 93 is a French department located north of the capital. It is especially known for being where the French state has piled up the emigrants who arrived in successive waves according to our need for manpower.

This population lives in housing estates, on the other side of the ring road. This department starts two meters from Paris but the ring of the peripheral still constitutes a mental barrier so much that these zones were considered second class. The lack of transportation, economic development efforts and real educational policies has taken more than 30 years to develop and even today the gap between these suburban areas and the urban centers is glaring.

The human, cultural and economic wealth that 93 contains is unjustly misunderstood, as the department is often confined - in the media in particular - to a land of news stories, insecurity and poverty. With this conviction in mind, in 2010, I proposed to create "93 Terre de Créations" within the framework of a call for tenders for public order for Plaine Commune a community of communes which brings together 9 towns of the 93.

This photographic collection of portraits makes places of history and culture dialogue with contemporary artists. It was exhibited at the Stade de France in 2011 and at the Gare du Nord the following year.

During this project, I was marked by the fabulous social, cultural and ethnic mix that makes up the identity of this territory and makes it so singular. Since then, I had hoped to bring to light, the richness of its identity character.

And it was in 2019 that I realized 93, Terre de Mixité, a photographic collection of portraits paying tribute to the ethnic-demographic diversity of this territory which counts 136 different nationalities, a record in France.

This project won the Plaine Commune call for tenders, which proposed a photographic carte blanche with hanging on the outside gates of the Stade de France. The exhibition, originally scheduled for March 2020, was postponed indefinitely due to the health measures in force.

Like pieces of a puzzle, these faces make up the face of Plaine Commune. Altogether, these women and men, one with the other, each at home and all on the same territory, draw the future of our present. My wish was to look at this reality and pay tribute to it, by putting these different cultures on the same level, literally and figuratively, in equality and fraternity offering everyone the freedom to be themselves.

The identity of the individual is the recognition of what he or she is, by him or herself or by others, in the image of a face-to-face.

click to view the complete set of images in the archive

Play Like A Girl

© Kate T. Parker

Play Like A Girl

© Kate T. Parker

I can't remember a time when I didn't want to play soccer. As a very little girl, sitting on the sidelines of my older brothers' games, I had one thought running through my head the entire 90 minutes: I want in. Whatever this game is... I want to play it. I wanted to be running and pushing and kicking and sweating and scoring. I wanted to be on that field. I had never seen any girls play, but that didn't bother me. When I was seven, I begged my mom to find me a team, and she did-and the moment I put on my uniform, laced up my cleats, and stepped onto the field for the first time, I was hooked.

Seven-year-old me was pretty impatient (so is 43-year-old me. Some things never change!). I was also loud, pushy, and aggressive, with a quick temper. That combination of personality traits didn't make things easy for me on a day-to-day basis, but on the soccer field, things were different. Those characteristics that earned me labels like "difficult" or "bossy" off the field actually helped to make me a good --no, a great athlete on the field. My coaches loved all the parts of me that other people tried to get me to soften or change. My loudness and pushiness helped me win balls and score goals ... and sometimes get yellow cards, but that's another story.

I am now a mother of two fierce soccer-playing girls (both of whom you'll see celebrated in this project), and I've coached countless others. But growing up playing soccer in the eighties, things looked very different. Female-only soccer teams were few and far between. We didn't see little girls wearing Megan Rapinoe and Alex Morgan jerseys to nationally televised games. Indeed, when I first started playing, I wanted to be just like my older brothers. It wasn't until high school that I came upon Michelle Akers in one of my soccer magazines, and then I wanted to be just like Michelle Akers, who was so good and so tough and so strong. Today, as a photographer dedicated to giving girls lots of good, tough, and strong role models, I get to photograph Michelle Akers!

And not just Akers, but Jessica McDonald and Carli Lloyd and more than a dozen other players who are following in the footsteps of Mia Hamm, Brandi Chastain, and Abby Wambach, who showed us just how amazing women playing soccer could be. And not just professional players, but athletes like my friends and former teammates Beth Foley and Amanda Riepe who helped pave the way for the next generation by being members of the first collegiate women's soccer team that their school fielded.

These days, it is estimated that 30 million women are playing the game worldwide. Look no further than the popularity of internationally revered players like Christine Sinclair (Canada), Ada Hegerberg (Norway) or Marta (Brazil) to see the global phenomenon of women's soccer. Listen to these women, and then to yourselves, because now it is your time. And that's what this project is about. Speaking personally, I can say that while I gave a lot to soccer (all that bottled-up energy!), it gave more back to me. The field and locker room (bus, training room, and long runs) were the classrooms where I learned the most about teamwork, sportsmanship, and determination- and they are all rules I continue to live by: Keep Your Head Up. Play to Your Strengths. Find Common Ground. Make Every Minute Count. I've learned that what your body can do is more important than what it looks like, that your teammates always will have your back and you should have theirs, that sustenance is key, and that it's important to recognize and celebrate what you're good at and not be afraid to show it off a little bit. As you review these images and see and hear from the many soccer-playing girls and women I've had the good fortune to meet, you'll find those very versatile lessons and more. Because no matter your age and no matter your experience, there are some universal truths when it comes to this beautiful game.

After photographing and meeting the amazing subjects in this project, I feel hopeful. Hopeful that our passions, like soccer, encourage us to be true to ourselves and live in pursuit of our dreams. By finding our voices on the field, we also find it off. It inspired me to remember my superpowers, and that although I don't play soccer as much as I did when I was younger, those qualities that made me stand out on the field, make me stand out as a mom, as an author, as a business owner, an advocate and photographer. This project helped me find my voice again and made me remember how much joy there is to be found within those white lines of the field.

There are so many voices telling us not to be who we really are. Sometimes it is hard to remember or figure out who that is. We don't have to listen to the "no"s or the "shouldn't"s. You can own your strength. You can celebrate it. You can play like a girl.

click to view the complete set of images in the archive

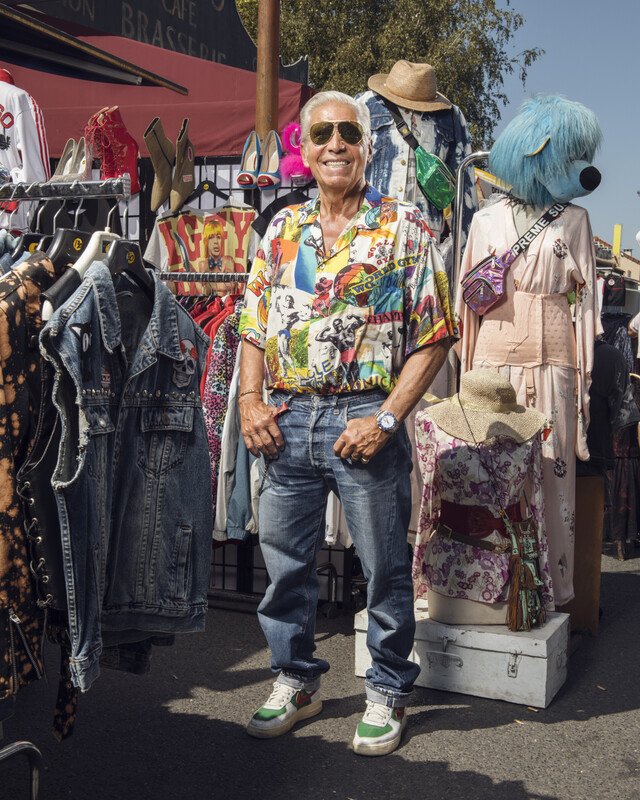

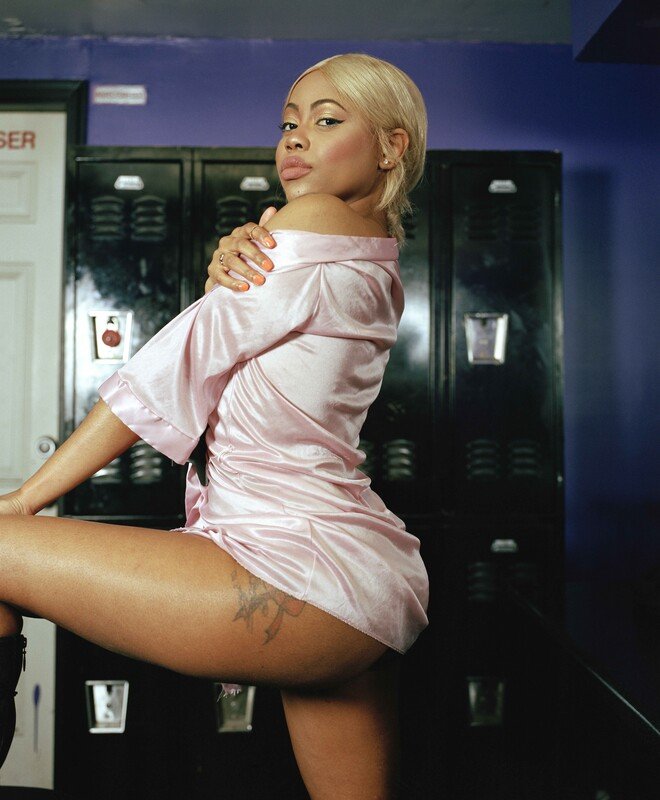

Atlanta Made Us Famous

© Hajar Benjida

Atlanta Made Us Famous

© Hajar Benjida

Atlanta Made Us Famous is an ongoing project that highlights the women that play an important role in the Atlanta hip-hop scene. During her first visit to Atlanta in 2018, Benjida interned at a photography studio right across the street from legendary strip club Magic City, which has been a crucial launch pad for numerous rappers’ careers. Realising that the female dancers in the club played a vital part in this scene, Benjida felt a desire to document their lives and experiences. She befriended several of them, documenting motherhood, and work and trying to understand the narratives and agency around their bodies. Her bold, tender portraits of dancers speak to an alternative, intimate, female-centred perspective – as mothers or mothers-to-be, for example. Through creating this series, Benjida hopes to show that their images “hold power and importance beyond hip-hop and its surrounding culture.’’

click to view the complete set of images in the archive

Coming Home

© Sasha Maslov

Coming Home

© Sasha Maslov

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has become a particularly brutal affair because of heavy civilian losses and the destruction of civilian infrastructure. Since Russia launched its full-scale invasion, more than 100,000 buildings have been destroyed. After six months of the war, civilian casualties are impossible to calculate. The confirmed toll is 5,587 deaths, but the actual number is much higher. In Maripol alone, Ukrainian officials estimate more than 22,000 perished based on the satellite images of mass graves, testimonies of those who have made it out of the city to Ukrainian-controlled territories, and available video and photo recordings. The indiscriminate bombing of apartment blocks and residential neighborhoods all over the country, as well as railway stations, public transport hubs, and shopping malls have shown the unprecedented brutality of the Russian Army.

Tragically, as the war has passed the half-year mark, people living in Ukraine are getting used to it. And while they continue to fight, many are trying to return to their routines, as the war becomes a haunting background to their daily lives.

In April, Russian forces were pushed back from the capital city of Kyiv towards the Belarussian and Russian borders. Recently occupied territories were returned under Ukrainian control, revealing the atrocities Russians have left behind. Mass murder, rape, looting–reports of the inhumane and barbaric ways the Russian Army has conducted itself covered the map of the region with red dots.

Horrifying images of people shot in the streets, with hands tied behind their backs, mass graves, and scorched land. The peaceful Kyiv suburbs of Bucha, Irpin, and Hostomel, which were, until recently, a haven for middle-class Ukrainian families, became a sprawling crime scene, where international war crime investigators were now pitching tents and establishing mobile command centers.

Destroyed houses in Irpin, Ukraine

And though the threat of Russians attempting to take Kyiv remained, many people felt it was time to come home. Since May, an increasing number of Ukrainians have returned, hoping that their houses are still standing. But some return only to find a pile of burned bricks and mortar.

The suburban town of Irpin saw some of the most brutal street fightings during the first days of the war. Because it wasn't taken, the Russian Army was unable to advance towards Kyiv.

Igor Soshnev, 54, stayed in Irpin the entire time. He was interested in cars all his adult life–he worked as a bus driver before the war and was known in town as the local car guy. Mr. Soshnev's most prized possession is a 1957 GAZ-69 , a Soviet all-terrain vehicle that he fixed up and kept in tip-top shape. He affectionately called it "My Gazik."

Igor Soshnev, 54 with his son Sasha, 17 at Igor's garage near the house that was destroyed by Russian artillery in March of 2022. Irpin, Ukraine

When the invasion started, he decided to stay. "I know this place like the back of my hand; I grew up here. I couldn't leave. I needed to stay and try to save it." Sending his family away, on February 25th, he went to a local military precinct with his friend Edik, the father of his goddaughter. The precinct, located in Bucha, is the next town over, but when they reached the building, they were told they didn't need volunteers.

Vova, a childhood friend of Mr. Soshnev and a veteran of the war in Donbas, stopped by the following day to check-in. Mr. Soshnev shared the frustration of being unable to volunteer, so Vova made a few calls and found out who needed people. In a few hours, Igor was issued an ID of the Irpin Territorial defense.

He hadn't held a gun since '86, the year he completed his mandatory Soviet Army service. Now he was holding a Kalashnikov again. "I felt like I was born with it," Igor recalls. He was assigned to man a

checkpoint near Bucha. On the 29th, he had his baptism by fire, a shootout with a diversion group that came close to the checkpoint. After the exchange of fire, the Russians retreated.

On the 29th, the shelling started to intensify. They had their first wounded, whom Igor transported in his Gazik to the hospital, after which they were given the order to retreat towards Irpin and then Kyiv. Scooping up his new battle buddies, Igor escaped his treasured vehicle via a half-destroyed railway bridge, hopping between mangled railway tracks, train cars lying on their sides, and pierced concrete.

A few days later, he decided to come back to check on his house and see if there was anything he could do in Irpin; he felt useless sitting around in Kyiv. He was planning to make his way back through the railway bridge, but he didn't know that Ukrainian forces had since blown it up. As he approached the bridge, he was stopped by the Ukrainian Army. A fellow with a code name Pokemon said that Igor wouldn't be able to make it to Irpin and that he was commandeering all vehicles for the needs of the Army.

Igor handed over his keys to Pokemon. Walking home wearing his bright reflective jacket from his GAZ-69 enthusiast club, he cursed himself for coming back.

That night he couldn't sleep, tossing in his bed thinking about what would become of his Gazik. The following day, he returned to the checkpoint, where he reunited with Pokemon, only to find out that the car was sent to Horenka to evacuate the wounded. It wasn't coming back–the tank division that brought it there had to abandon it.

Igor Soshnev, 54 and his wife Oksana Soshneva, 47 at the site of their destroyed house in Irpin, Ukraine

Horenka is 8 km away. Igor decided to walk into the unknown to retrieve his Gazik along what was an extremely ambiguous separation line between Ukrainian and Russian troops. Artillery shells flying over his head, Igor walked to Horenka to recover his most treasured possession. And there it was, sitting on the side of the road, among the rubble of recent shelling and burning buildings–all in one piece, key in the ignition.

All car and railroad bridges to Irpin were blown up by then. Only one pedestrian bridge remained, not too far from where the railroad bridge stood a couple of days before.

Igor went on to check the dimensions of the pedestrian bridge. The Gazik could fit. The old 4x4 climbed the stairs of the bridge and made it through. He returned to his house in Irpin, and from that day, started running evacuations between Irpin and Kyiv. "I would do 6-7 runs a day. I was the only one that could do it. I would take as many people as I could with me to Kyiv and bring back some food, or whatever volunteers would give me there," Mr. Soshnev says. Local people nicknamed his route "A road of life."

On the night of March 21st, the first mortar landed on his house. It has hit the roof and damaged a room on the second floor. The explosion didn't wake him. The next day the house was hit again. This time he was lucky he wasn't inside–a projectile hit his home directly. He was in the garage and was knocked down to the floor. Running outside, he saw his house in flames. There were no emergency services to call. The house burned down in front of his eyes. His Gazik, which was sitting in the driveway, was destroyed.

Igor Soshnev's 1957 GAZ-69 after restoration parked on the driveway next to his destroyed house in Irpin, Ukraine

"I was sitting on the sidewalk praying. I was hoping the flames wouldn't spread to the garage. That's all."

In April, Igor's wife, Oksana, 47, and his son Sasha, 17, returned home. The word about Igor's heroism has spread and the townspeople, his neighbors, friends, and people he has never met started offering help to restore Igor's Gazik. With spare parts from the Gaz-69 club and an old Volga engine, he and seven local mechanics fired up the Gazik once more on May 4. On May 8th, Igor rode through Irpin with a Ukrainian flag mounted on the roof.

Soon after, and across the street, Yurii Sikan, 59, and Darina Mikhailishina, 51, returned to their home to find it destroyed. They were two of the many people Mr. Soshnev transported via the lone pedestrian bridge. When the war started, they, like many other peaceful Ukrainians, couldn't believe they could be a target. This all changed during the first days of March when Darina saw Russian fighter jets flying low over their house, dropping bombs on nearby residential areas. They immediately decided to flee.

On March 25th, when they were in Uzhhorod, a town in Western Ukraine close to the Hungarian border, their neighbor contacted them with sad news. A missile had hit their house, and it was gone. On May 15th, Darina and Yuri returned, along with their cats. "They understand where they are but are very confused," says Darina "they know the door should be here and a window there, but it's all gone."

Their neighbor, a woman, named Tetiana, posted the couple's story on Facebook. Shortly after, a man they didn't know from the Poltava region donated a camper and drove it to Irpin. The trailer is now parked in their driveway. Darina, Yurii, and their cats all live in it, hoping to one day rebuild the house.

Yurii Sikan, 59 and Darina Mikhailishina, 51 standing in what used to be the kitchen of their destroyed house in Irpin, Ukraine

"When we came back, we saw that there was nothing left. Nothing. All memories, all our work, pictures of Yura's parents. It's all gone. All gone..."

As Winter approaches Darina and Yurii are seeking a new place to stay as the trailer will not be a reliable shelter during the cold. They put their names on a list for temporary shelter. As the government and city officials try to find a solution as to where to house thousands of people, Daria and Yurii's ticket most likely won't be drawn, as priority will likely be given to families with kids and those who have lost family members in the war.

Just a couple of blocks away was a co-op building with a cheeky name, Dub-ok (Dub means Oak in Ukrainian, and Ok still means Ok). Volodymyr Husak, 28, serves as head of the building's tenant

association. Co-ops have become quite popular in suburban communities like Irpin, where middle-class families and young professionals settled as Kyiv grew more and more expensive. Mr. Husak was elected the head of his co-op in 2018 and managed the 44-unit building while working as a freelance system administrator in the IT field.

On February 24th, Volodymyr woke up at 5 am with a strange sense of uneasiness. A few minutes later, he heard jets flying over his apartment. Then the sounds of explosions. The ground was shaking. He understood that the war had started. "I called the family. Then I opened the building chat and messaged everyone to stay away from windows and seek shelter". At 10 am, he went to a meeting at Irpin's city hall where it was to be decided what to do.

Volodymyr Husak, 28 at one of the apartments in the Dub-ok co-op building in Irpin, Ukraine

About half of the tenants from Voldymyr's co-op had fled on that date, and those who remained slept on the basement level in the make-shift bomb shelter. Volodymyr himself volunteered to distribute humanitarian aid that started arriving almost immediately from Kyiv and helped with evacuations. "First days I barely slept," he remembers of the first days of the war.

By March 4th, only seven people remained in the building. On March 5, Mr. Husak was returning from Kyiv and was denied entry back to Irpin by the Ukrainian military–street fights with the Russians had reached the center of town. He went to Bila Tserkva, a small village near Kyiv. He continued volunteering, organizing evacuations from Irpin via phone, and arranging humanitarian aid and food delivery to the areas where it was possible.

On March 5th, the apartment building was shelled. Five people were inside, and luckily none were harmed. One of them ran outside and called Mr. Husak. With the words "the roof is burning..," the cell service cut out. He couldn't reach any of the neighbors after that.

When the Russian Army retreated from the area and the town of Irpin was relatively safe to return to, Volodymyr started commuting back and forth daily. His work now consisted of helping people who wanted to return and start rebuilding. He later moved into his friend's home in Irpin, which survived the invasion.

Destroyed Dub-ok co-op building in Irpin, Ukraine

Recently, the tenant association calculated the repair cost, which amounted to 18 million Hryvnias, about half a million USD, an impossible amount for the residents of Dubok co-op to raise. The government doesn't have the means or resources to start repairing buildings like theirs as the war still rages on in other regions of Ukraine. Mr. Husak is looking for a solution to curb the damage and hopes for government assistance in the future. "Once the legislative process is in place we're gonna decide what to do. Right now the war is still on so I don't have much hope the government will have the money for rebuilding."

On the other side of Irpin sat the building where Yulia Nelubova, 44, bought an apartment for herself and her three children nine years ago. Yulia is a singer who has been with the Veryovka Ukrainian National Folk Choir for 20 years. The chorus was planning its upcoming tour season just before the war started.

Now, standing in the middle of her burned-out apartment, she is in disbelief. "Maybe it's a defensive reaction, but I can't fathom all this. It seems unreal. Like I will wake up tomorrow, and it was all a bad dream," Ms. Nelubova says. But unfortunately, it is real. Her first-floor apartment bought as a sanctuary for her family, is gone.

"I am still drawn here," she says of the town of Irpin, its parks, and abundance of nature. When the full-scale invasion began in February, Ms. Nelubova didn't want to leave. Even after the internet, electricity, and water were cut off, with fighter jets flying low over her building, she still resisted the idea they could be harmed. "You say to yourself, it's nearby, it's not gonna touch us," she recalls of the first days of war.

On March 25th, she received a text message from a neighbor with a video of their house smouldering. "At first I thought it's the other side [of the building] but then recognized my apartment... My heart dropped." Ms. Nelubova was in Vinnytsia oblast in Western Ukraine by that time, but she couldn't find peace. Leaving the rest of her family in safety, she returned to Irpin shortly after it was liberated.

Yulia Nelubova, 44 in her apartment that was destroyed by Russian bombings of Irpin, Ukraine

"We got a generator from our boys from the Territorial Defense, had some coffee with neighbors sitting in front of our burned-out building," Mrs. Nelubova talks about the first hours of her return. And even though her spirits were high, her heart was broken. When she came back home, she was still hoping to find some things intact. But everything had burned.

"I couldn't even cry anymore. I was just standing in the middle." Yulia sews her traditional dresses, and in the apartment, there were many garments she treasured, ones she made herself and others she inherited. The most prized possession in her family, a traditional wedding dress that belonged to her great great grandmother, has burned with everything else. Besides the heirlooms and personal possessions, she lost a year's worth of medicinal supply for her oldest son, who is recovering from cancer and suffers from Hepatitis B.

Now her kids have returned, as well as her 70-year-old mother. They rent an apartment nearby. When they moved, it had no windows left. All of the glass had been shattered by shelling. In Irpin, like in many other towns that saw heavy combat, items in high demand include window glass, doors, plywood, and tarps. Local window shops are working non-stop to salvage glass and repurpose it. Iryna found a man who to patch together some double-glazed windows from bits and pieces that he had collected from destroyed buildings.

A Ukrainian health agency found some medicine for her son, and her chorus started collecting money for his continuing treatment. Ms. Nelubova is still in disbelief but reassured by the strength and kindness of the people around her.

A pile of burned and destroyed vehicles near Bucha, Ukraine

Irpin became a stronghold that Russian troops failed to breach, but it still suffered greatly. Oleksandr Markushyn, the mayor of Irpin said that 70% of the town had been destroyed due to fighting, mainly from Russian shelling. Now the city is planning to buy out an apartment complex from a developer to start resettling affected families and build several new buildings. As of August 22nd, the Irpin town council was preparing to settle the first 29 families, prioritizing those who had lost family members in the war.

As the war is still highly hostile across the front line, which stretches almost 2,500 kilometers, the Ukrainian government hasn't developed a specific plan to start rebuilding the residential areas. Affected cities or towns take the initiative and try to devise either temporary solutions.

In Bucha, the town separated from Irpin by a short drive, one of the first modular housing complexes is now operational and hosting over 300 people. It's not nearly enough to accommodate everyone who has lost their homes. Bucha suffered from the Russian occupation immensely; almost 1500 houses and 250 apartment buildings were either damaged or destroyed. Bucha also carried the heavy toll of civilian population casualties and continues to be an active site of an investigation into shocking war crimes perpetrated by the Russian forces.

A small suburban town of about 28,000, Bucha has become an attractive place to start a family. Alla Serebina and Andrii Kuziukov moved into their first apartment three years ago and have slowly decorated and fixed things up. On the evening of February 23rd, they were online shopping for a new chandelier for the kitchen.

"This is our family nest," Alla says, "Our soul."

Alla Serebina, 26 and Andrii Kuziukov, 33 with their dog Utah in the apartment in Bucha, Ukraine

Alla and Andrii were sitting in their kitchen searching for a chandelier online. Not finding one they could order, they made plans to go shopping the next day. Less than 4 hours later, they were woken by explosions.

Hostomel, a town a few kilometers away, had encountered the first heavy fighting because of its airport, where Russian paratroopers were attempting their first landings and assaults. Alla and Andriy, were now looking at Russian helicopters trying to land in Hostomel. The windows were shaking from explosions, gunfire crackling in the darkness of the night. Utah, a rescue dog they adopted two years ago, was barking.

A feeling of complete loss has overwhelmed them. Panicked, Alla and Andriy started throwing things in suitcases. Shortly after, they were sitting in standstill traffic, trying to leave Kyiv on the chaotic morning of February 24th. After staying with eight other friends in Vinnitsa Oblast for a couple of days, they headed further into Western Ukraine where a family friend offered them refuge.

They were able to breathe out for a short while. But Andrii's father decided to stay in Bucha, which was now occupied with no cell or internet service. Andrii tried to find out every day if his father was still alive. "You just ask anyone you can get ahold of somehow, through however many connections, if they saw him. It was awful." Luckily, he survived. Later, when Andrii and Alla returned, he told them he had been detained by Russian soldiers twice.

Towards the end of March and beginning of April, images of Russian atrocities in Bucha were circulating on every media outlet. Alla and Andrii were pained to realize that their hometown would never be the same.

Utah, a 2 year old rescue dog of Alla Serebina, 26 and Andrii Kuziukov, 33 at their bedroom in Bucha, Ukraine

"When I saw those images, my reaction was complete disbelief," Alla says. "Everyone was reposting pictures. I just wanted to shut myself down. I couldn't believe that other humans can do that to other humans... How is it possible? They live in towns like ours, they have houses, they have families. How could they do this? I'll never understand that."

Once the Russian Army left Bucha Andrii's father went to their apartment. They already knew that would be damage. Their security system had sent them an "intrusion" warning shortly before the internet disappeared, but they had no idea the scale of the damage.

Most likely, a tank round was shot at their building, went through the window and three walls, and ended up stuck between the bathroom tiles.

"We wanted to redo the bathroom anyway," says Andrii.

Russian paratroopers attempted to land in Hostomel on the first day of the full-scale invasion planning to launch an attack on Kyiv while using the airport as their base. Oleg Golovatyj, 44, lived with his family in the apartment he inherited from his father. His father was an officer in the Soviet army, and Hostomel was a closed military town where many military families settled after being awarded apartments by the Soviet State. After Ukraine gained its independence in 1991, Hostomel was opened. The former army base became home to the Antonov planes, including the biggest cargo aircraft in the World, Mriya, which was destroyed by the Russian attacks on the airport.

Oleg Golovatyj, 44 in what used to be the living room of his family's apartment in Hostomel, Ukraine

Oleg's family lived just a block from the airport, making his house vulnerable to potential shelling. Coming from a military family, he understood they had to leave immediately. He first took his family to Bucha, where they had a little cottage. But it wasn't safe there either.

Mr. Golovatiy is a civilian and worked as a repairman at the local military unit, the same unit where his father served. That made him vulnerable. Russians entered Bucha on February 27th, and soon after, Russian soldiers were knocking on the door of their dacha. "I have to say they were overly polite and gave us instructions on what to do or what not to do," says Oleg about the interaction. They were told that they wouldn't be harmed if they adhered to the occupation rules, and that it would all be over soon.

The next day, they decided to head toward Kyiv. The family got into Oleg's 1999 VW Golf 4 Universal without knowing the situation on the road. His wife Yelena and their son Sergii, 13, his elderly mother Nadezhda Ivanivna, and himself, headed into the unknown, joining the caravan of cars trying to leave familiar streets now littered with shrapnel and broken glass. Burned-up tanks smoldered, and civilian vehicles, riddled with bullet holes, were strewn about the road like toys.

They had no idea what lay ahead. On the way, they saw bodies lying by the side of the road, destroyed buildings that had still stood a couple of days ago. The first Russian checkpoint was the worst, Oleg says. "It was Buriats, they made me take off my clothes, searched everything, went through my phone, and threw away the sim card ." Oleg had already cleaned up his phone, deleting all contacts associated with the Army base he worked at, pictures with Ukrainian service members, and anything else that may have given away his military affiliations.

Abandoned sleeping bags in the basement of a partially destroyed apartment building near Antonov airport in Hostomel, Ukraine

The trip to Kyiv, which would typically take about half an hour, took all day, but they made it out. Oleg remembers the moment he saw the first Ukrainian checkpoint, tears rolling down his cheeks, "We got out."

Once Oleg and his family reached Kyiv, they were met by a friend who let them stay in their apartment for a week. Oleg's family then left for the West of Ukraine, but he stayed behind, enrolling in a local Territorial Defense unit. Yelena was upset, even offended.

In Kyiv, a stranger discovered they needed a place to stay and offered an empty apartment. On arrival, volunteers gave Yelena and Sergii free clothing, and Oleg's mother was provided with necessary medicine. Oleg was overwhelmed by the kindness shown to him and his family, and now, looking back, he posits, "I sometimes think to myself if I would ever let a total stranger just move into my place."

On April 14th, Oleg returned to Hostomel. He found out that his house had been destroyed earlier in March when he saw satellite images posted to one of the town chats and videos from neighbors. Oleg hadn't had time to mourn his family apartment among all the commotion. When he finally saw it with his own eyes, the sadness overwhelmed him. "All was gone. But mostly my heart was breaking for my son's drawings. He really treasured them. Even won a contest..."

On the other side of the Romanivsky bridge sits the village of Horenka. Horenka was never occupied, as the Russian Army couldn't cross the bridge, which became a symbol of Kyiv's defiance. But that was not enough to spare the village from intense shelling.

Velentyna Briakana, 55 and her dog Bucks in the destroyed apartment they used to live in before the Russo-Ukrainian war. Horenka, Ukraine

Velentyna, 55, lived in her two-bedroom apartment with her son, daughter with her husband and three grandchildren, and a recently adopted puppy named Bucks. On March 4th, during the mandatory evacuation, they all jammed into one car driven by a volunteer from Kyiv but had to leave Bucks behind. He cried, running after the car as it joined the stream of vehicles heading towards Kyiv. For her grandchildren, it was a crushing heartbreak.

They were evacuated to the Khmelnytsky region. A local family gave them a house and provided food and necessities. And at the end of March, she received a text message from her neighbor that said, "Look what has happened to your apartment," with a few pictures attached. She saw a hole in the building where her apartment used to be. Earlier it was hit by a Russian mortar shell, which landed right in her living room. Just a month ago, she was playing with her grandkids there. Valentyna broke down in tears, wailing.

"I worked for this place all my life, and it's gone in one split second, " she says, standing in the middle of the rubble, pointing out where their belongings had once stood. Bucks, excited every time she visits, leaps from the front door, which now lays mangled on the floor, into what used to be the living room.

Valentyna, who returned at the end of April, now lives in Kyiv. The building where she works as a concierge provided her with a room. She comes to Horenka to take pictures of her scarred building to start the process of filing for government assistance as a person who has lost their home.

According to Iryna Vereshchuk who serves as a Minister of Reintegration of Temporarily Occupied Territories, more than 800,000 are unable to return to their destroyed or damaged homes. According to multiple officials, the Ukrainian government is working on implementing systems to track the damage and is planning to restore as many as they can. But tens of thousands of Ukrainians will never be able to return to or raise their homes.

Katya Baranivska, 22 standing in front of the destroyed building where her family's apartment used to be before it was destroyed by a Russian bombing. Borodyanka, Ukraine

One of them is Katya Baranivska, 22. She is standing in front of the apartment building where she grew up. She moved out just two months before the building was destroyed, renting a small flat a couple blocks away in Borodyanka.

Borodyanka, a town of 12,500 residents, is about 30 kilometers away from Irpin towards the Belarussian border. On February 26th, the air rides began in Borodianka, and the first bombs were dropped on the village. On that day, as Russian tanks approached the village, facing resistance from the town's Terriortial Defense units, Katya's family hid in a bomb shelter under a local school.

On March 2nd, their home was bombed. "We understood at that point that there is nothing else for us here and decided to leave," says Katya. As her father drove out of Borodyanka, Katya watched the crater smolder in their apartment building. An hour ago, it was intact; now, a Russian missile had destroyed the home she made her first steps.

Destroyed buildings in Borodyanka, Ukraine

"It was very. hard for all of us. Very hard..." says Katya about the day they were leaving. "But we were all together, so that's what really mattered."

They headed for Vinnytsia. The ride was silent. Katya, her parents, and her boyfriend left the town where they spent their whole lives without knowing what would come next. In May, after Borodyanka was de-occupied, they returned.

"It's very difficult to come back," says Katya about returning to the site where her parent's home was destroyed. "All our family memories, pictures, heirlooms - it's all destroyed ."Katya couldn't bring herself to go near the house after returning to Borodyanka. She attempted to walk over several times and observed from a distance until one day, clutching her fists, tears in her eyes; she walked into what used to be their courtyard. Her parent's bedroom in their eighth-floor apartment was exposed on the side of the building like an open wound. The bed was still made.

click to view the complete set of images in the archive

The Sami claim they pay the price for Sweden going green

Text © Klaus Thymann + Karen McVeigh

Photos © Klaus Thymann

The Sami claim they pay the price for Sweden going green

Text © Klaus Thymann + Karen McVeigh

Photos © Klaus Thymann

‘We borrow our lands from our children' Sami says they are paying for Sweden to go green

Indigenous reindeer herders fear the drive towards a more sustainable economy is destroying their traditional way of life and identity

It’s just after sunrise near Jokkmokk, a small town north of the Arctic Circle in Sweden, and Gun Aira, a reindeer herder, and her family are gathering the animals for the long trip to the mountains. Following the reindeer’s spring migration through hundreds of miles of snow-covered forests, to their calving area close to the Norwegian border, is a centuries-old tradition.

But today, the reindeer, capable of one of the longest land migrations on Earth, will travel the 150 miles (250km) to their calving grounds by road, in the back of a big lorry. Aira, who recalls skiing alongside the reindeer in her youth, says moving them by foot is now impossible here, due to a habitat diminished by development. “A lot has changed,” says Aira, from the Sirges Sami community, the largest of 51 semi-nomadic herding groups in Sweden. “The landscape is much more fragmented.”

In Sweden’s Arctic north, the Sami (or Sámi), one of Europe’s most distinct Indigenous communities, are facing the loss of their culture, livelihood and identity, they say, due to a failure to respect their rights. Forestry and large-scale hydropower – 80% of which is on Sami land – have shrunk winter grazing areas. Sixty years of logging and clearing has meant forests rich in lichen, traditional grazing for reindeer, have declined by 71% in Sweden. The herders’ most significant challenge now, Aira says, is to “get enough food for the reindeer, to find grazing areas that are connected. It is almost impossible to feed them from nature only.”

The climate crisis in the Arctic, which is warming three times faster than the rest of the world, is also disrupting grazing. In warmer winters, melting snow turns to ice on the ground, which traps lichen underneath, further cutting off the reindeer’s food supply. In winter, Aira has to supply food for the reindeer, a species that has survived in this harsh landscape since the ice age.

“People don’t seem to understand – we are changing our nature,” says Aira, whose two grownup children are part-time herders. “How long can we keep doing this?” Fewer than 10% of Swedish Samis are herders, but they are considered the custodians of Sami identity, culture and way of life. Without the reindeer and the land on which they depend, but do not own, the Sami people would not exist, Aira says.

“During the war, we supplied food for Sweden,” she says. “Now, they are in danger of losing a people – the only nature-people they have.” An estimated 50,000 to 100,000 Sami live in Sápmi, formerly known as Lappland, which spans parts of Sweden, Finland, Norway and Russia.

Sweden is renowned for its gender equality, extensive social safety net and progressive stance on the climate crisis. It has invested hundreds of billions of kronor in its northernmost counties, Norrbotten and Västerbotten, where Hybrit, a fossil-free steel initiative, and H2 Green Steel, two coal-free power plants, a gigafactory for electric vehicle batteries, and a host of windfarms to power them, are planned.

But a growing backlash against the country’s green transition and its effect on the Sami people shines a spotlight on its failure to uphold Sami rights.

In March, the environmental campaigner Greta Thunberg denounced as “racist and colonial” Sweden’s decision to grant a permit to a British company, Beowulf Mining, for an opencast iron-ore mine in Gállok, because of its impact on the Sami people. UN rapporteurs have condemned its failure to obtain the prior and informed consent of the Swedish Sami, over the irreversible threat it poses to their lands, livelihoods and culture.

In December 2020, the UN committee on the elimination of racial discrimination (CERD) concluded that Swedish law discriminated against Sami. A legal opinion held that legislation did not enable free and informed consent for the Sami in the permit-granting process for mining concessions.

Unlike Norway, Sweden has not ratified the 1989 indigenous and tribal people’s convention, which would uphold Sami rights. It only formally recognised the Sami language in 2000. Jenny Wik Karlsson, senior legal adviser for the Swedish Sami Association, and the Swedish Society for Nature Conservation are considering legal action against the government’s decision to grant a permit at Gállok.

“It is not over,” Karlsson says. The first option is a formal complaint to the supreme court of administration, to examine whether the government has fulfilled its legal obligations. Then the case might be taken to the environmental court.

The case is “symbolic”, says Karlsson. “It gives a clear view of how they are looking at Sami rights. If the government won't say no in this case when it is a non-critical metal and they had the opportunity to say no, it is a green light for other mines as well.”

Half an hour’s drive from Jokkmokk, Mikael Kuhmunen, president of the Sirges Sami, points across a snowy lake to the proposed site of the Gállok pit.

“I’m far from the mine, but like ripples in the water, it will affect me,” Kuhmenen says. “Everything is worse than we expect. If reindeer are migrating and see something that scares them, they turn around and go back. “They talk about the green transition. But the reindeer, and we, are paying the price.”

In March, researchers at the Stockholm Environment Institute, who examined three mines in northern Sweden, concluded that predicted impacts on Sami communities were “grossly underestimated” and continued after a mine’s closure.

Beowulf Mining argued the pit would benefit Sweden’s green transition, by ensuring a domestic source of iron for coal-free steel. The mine was in the public interest, the government said, and permission included “far-reaching conditions” to counteract disturbances to reindeer husbandry, and commitments to pay for lorries for migrating animals, compensate herders, restore the land afterwards and consult with those most affected, the Sirges and Jåhkågasska tjiellde Sami herders.

Kuhmunen has little faith in the process. “I saw a movie with Bruce Lee, where he talked about water being shapeless,” he says. “You put it in a cup, it takes the shape of the cup. We are like water – we are expected to adapt ourselves. But no one listens to us: it’s like pouring water on a goose.”

The 100km drive north from Jokkmokk to Gällivare is a blur of green and white. Forests give way to frozen lakes and rivers and back to forests again. The road winds past several big hydropower plants, with their mass of steel pylons, before skirting Muddus national park, with its ravines, waterfalls and centuries-old forest, home to brown bear, lynx and wolverine. The park is part of a Unesco world heritage site.

This stunning landscape is part of why people from Sweden’s more populous south move here, but working in the mines and associated industries is another big pull.

Nine out of 12 mines in Sweden’s north are located on Sami land, including the largest iron-ore mine in the world, in Kiruna, and one of the EU’s largest copper mines, at Aitik, outside Gällivare. In February, the supreme court gave the Aitik mine the green light to expand, despite opposition from herders and environmentalists, with a new, 1km-long pit.

“There will be a new industrial landscape which will affect us,” says Roger Israelsson, 65, of the Ratakivare Sami community outside Gällivare. “The expansion has had to compensate for the loss of land.” Israelsson estimates that 60% of his community has given up herding since he was young. His daughter, Susanna, 30, says: “People see the land here as wilderness, as uninhabited. But they are Sami lands. We are taught that we are borrowing our lands from our children.” The promise of new jobs the green transition will bring has polarised communities.

Lotta Finstorp, governor of the county administrative board of Norrbotten, Sweden’s northernmost county, says: “Green ambassadors from all over the world are queueing to come here. Not so long ago, nearly everyone knew someone who had to move south to get a job. “We need 100,000 more inhabitants in Norrbotten and Västerbotten for the green industries. If not, we will fail.”

Asked if the decision to grant a permit for Gállok may have affected Sweden’s reputation internationally, she says: “Gállok was hugely polarising. Perhaps it has given pause for thought.” At a new housing complex in Gällivare, built by LKAB, an international mining company, residents say they are well looked after by the firm. Mairi Johansson, 45, whose boyfriend worked at LKAB, used to live in nearby Malmberget, before a large sinkhole developed. The company moved her and other residents to Gällivare last year.

“I’m happy with the mining industry,” Johansson says. “If there was no mine, there would be no Gällivare. I’m a lot safer here in this new place. I was afraid of falling into that hole, it was a risk zone. When they had explosions, my walls would shake.”

click to view the complete set of images in the archive

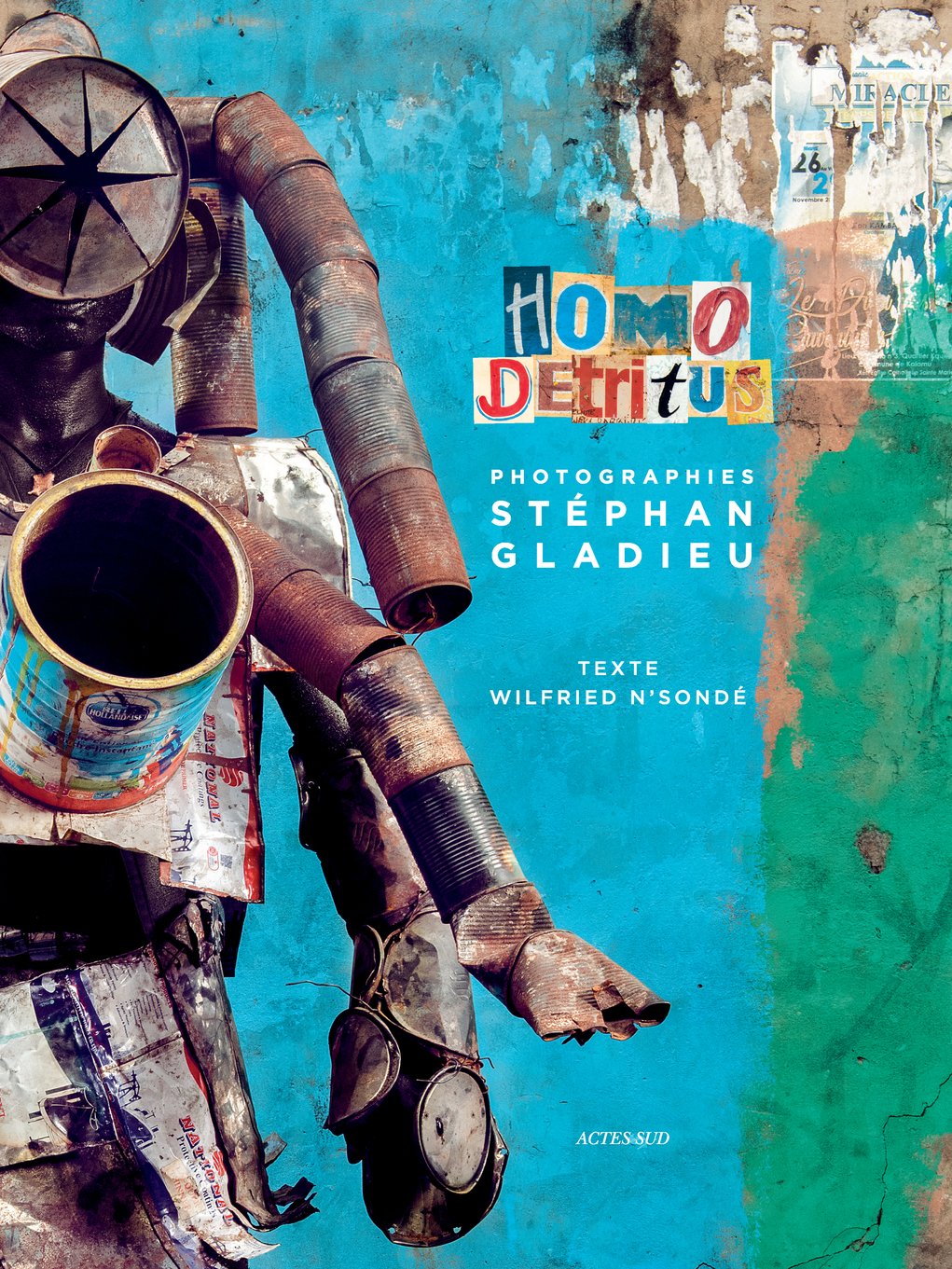

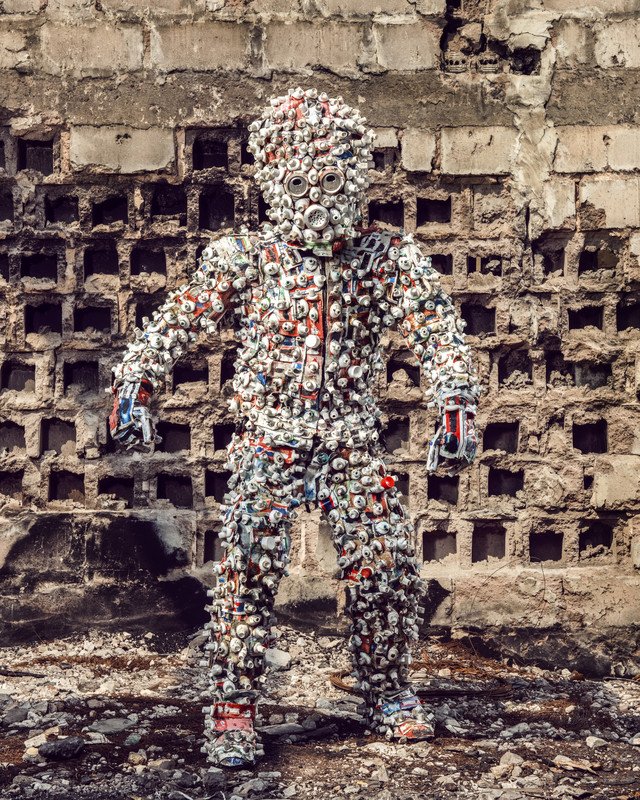

Homo Detritus

© Stephan Gladieu

Homo Detritus

© Stephan Gladieu

On the waste of Kinshasa

Publisher: Actes Sud

September 2022

24.00 x 32.00 cm

104 pages

ISBN : 978-2-330-16748-6

Photographs © Stephan Gladieu

Text © Wilfried N'Sonde

A recent study by the INRAE, a research institute for the environment alerts us to the worrying invasion of plastic. Since its appearance in 1950, plastic has conditioned all our daily life. And if at the time nobody was worried about the heap of waste, today humanity is totally addicted to it. Today 13 billion tons of plastic waste are scattered around the world. In 2050 it will be 50 billion tons.

This global problem primarily concerns the poor countries that are becoming the world's garbage cans because the rich countries that are at the origin of their production have them taken over by the poor countries that are becoming the planet's landfills.

The second largest country in Africa, the Democratic Republic of Congo has one of the richest subsoils in the world in gold, coltan, diamonds, cobalt, oil ... and yet remains the 8th poorest country on the planet.

The DRC is a geological scandal.

For decades, like many African countries, Congo Kinshasa has seen its wealth exploited by international companies - mainly Chinese - in a commercial process resembling a new "raw materials syndrome". The lack of commercial equity in the mining and oil sector, the country's increased dependence on China combined with massive corruption by successive governments since decolonization, prohibits any equitable redistribution of the product of natural resources.

The poverty rate affects nearly 65% of the population. Life expectancy at birth is only 48.7 years and the school enrollment rate is 55% for a population of which 60% are under 20 years old.

The Congolese are among the biggest losers of globalization. They very rarely benefit from manufactured products that draw on their country's resources. In general, these products reappear in Africa in the third or fourth generation; at best they are obsolete, but more often than not, they are only waste products from industrialized countries that prefer to relocate their treatment. Kinshasa's slums are very often built on land filled with tons of untreated waste.

"What is born of the earth returns to the earth," Euripides used to say... In the DRC, we have corrupted the virtuous circle by transforming a feeding ground into a garbage can.

Another paradox: from this waste that is burying the slums of Kinshasa has just been born an artistic movement that borrows a lot from the approach of Arte Povera, the protest movement of the consumer society at the end of the 1960s in Italy. It cries out its urgency to live and no longer survive in the garbage and injustice of the world.

Cell phones, plastic, corks, synthetic foam, inner tubes, fabrics, electric cables, syringes, capsule boxes, car parts, cans, everything is the raw material - and yet already industrialized! - to denounce the chaos in which the Congo is kept.

Covered with a full mask made from this garbage, a generation of artists rises up and federates in a collective that thirsts for a claim, a primary and visceral necessity to create and denounce.

If the Congo has partly lost its animist and mystical traditions, dissolved under the pressure of the Catholicism of the former Belgian colonists, these young artists are returning to the traditional source of the African mask. An inhabited mask, bearer of a spirit, a symbol of an overflow.

This collective is "Ndaku, life is beautiful", founded six years ago by the visual artist Eddy Ekete. Today it brings together nearly 25 artists, almost all trained at the Academy of Fine Arts in Kinshasa.

Painters, singers, visual artists and musicians, have united to denounce the tragedy of their daily lives, the wars that have resulted, the exploitation of women and men that results from it and ferments the unfathomable misery that deprives them of all dignity.

Originally, these artists had one thing in common: they had no resources, no support. Inhabitants of the slums, are naturally found in the garbage an abundant and free raw material. It was Eddy who created the first mask, paving the way for the young artists around him.

The collective welcomed me for two weeks to carry out this artistic project, which is a continuation of my work. I remained faithful to my photographic bias by choosing to make the portraits in the streets of Kinshasa, the setting and the character responding to each other.

The street is the common history of these artists. Their collective organizes street performances to raise awareness of the authorities and the inhabitants. It was, therefore, legitimate to place them in the reality of Kinshasa's ghettos.

All these photographs were taken with the written agreement of the collective and each artist. This work was done in total collaboration with them and I have therefore the authorization to diffuse and broadcast this series of portraits. I continue to support their work by promoting it to institutions and international cultural services.

It seems essential to me to recall that this problem of waste management and exploitation of raw materials is not limited to the Congo but concerns a large part of Sub-Saharan Africa, West Africa and Central Africa.

While some African countries are struggling to manage their waste, they are also recovering it from abroad.

Many industrialized countries send their waste to African countries, mainly because companies that use plastic in their products or packaging do not pay for recycling. In the U.S. and other countries, this has forced municipalities to bear the costs of collecting, transporting and processing plastic waste.

This burden remained "hidden for decades, mainly because about 70 per cent of this waste was exported to China," she continues. But in 2018, Beijing closed its doors to much of America's plastic, and some U.S. cities discovered they couldn't afford to recycle it. So they gave up on doing so.

Under the Basel Convention, which came into effect in 1992, countries cannot export their toxic waste without the consent of the recipients. This is why countries exporting end-of-life e-waste to Africa do so under the guise of a "charitable" donation: the objects transported are considered second-hand goods, in other words, second-hand electronic materials, which are, in turn, authorized. "In this sense, we find that the Basel Convention relieves France of its responsibility in its ability to find treatment solutions on its own territory," according to Nicolas Garnier, CEO of AMORCE, an association of local authorities specializing in waste management. He adds that this is due to the fact that "no one wants an electrical or residual waste treatment facility close to home".

As a result, the continent is flooded with waste. Uncontrolled landfills are appearing and several countries, including Ethiopia, Congo, Burkina Faso, Mozambique, Mali and Niger, see their dumpsites overflowing with household waste but also with toxic materials or electronic equipment from developed countries.

click to view the complete set of images in the archive

How Do You Prepare for a School Shooting

Photographs © Lindsay Morris

Text © C.J. Chivers

How Do You Prepare for a School Shooting

Photographs © Lindsay Morris

Text © C.J. Chivers

The New York Times magazine commissioned the story and published it on July 3rd.

Some students remembered the unceasing screams of children calling for help, or the sight of peers wailing over seemingly lifeless friends. A parent recalled her rising discomfort over how realistic the artificial wounds and blood appeared to be. A fire chief marvelled that one student performed the role of a despondent teenager so well that she fooled him and three other first responders into thinking she needed real medical help, and left an emergency medical technician in tears.

On a Saturday in early June, less than two weeks after a shooting in a school in Uvalde, Texas, killed 19 students and two teachers, the village of Greenport, N.Y., a small coastal community on Long Island’s North Fork, held a regional exercise for first responders to sharpen their handling of a crime that in recent years has become common enough to enter crisis-response routine. The exercise at Greenport High School, which organizers said involved 62 simulated victims and roughly 240 first responders from multiple public-safety agencies and firefighting districts, was not directly related to the delayed and bungled handling of the shooting in Uvalde. It had been part of the local fire chiefs’ agenda since early January when First Assistant Chief Alain de Kerillis of the Greenport Fire Department proposed putting the simulation on the year’s training calendar. The world we live in now, he said, requires preparation so that departments will be logistically and psychologically ready. “Thirty years ago, back in the late ’80s and early ’90s, we just fought a fire and had a couple of beers afterwards and said, ‘Oh, this is great,’” de Kerillis said in an interview at the fire station in mid-June. “Something is really wrong with what’s going on. So how do you mentally prepare?”

Data on the frequency and scale of mass-shooting simulations at schools are scarce. School districts and public-safety agencies have held them at least since the murders of 27 people in the Sandy Hook Elementary School shootings in Newtown, Conn., in 2012. Using stress and a degree of realism, they build on the now-common — and often legally mandated — lockdown drills held in schools throughout the land, in which students and staff members practice quietly sheltering in classrooms or other parts of a school to limit exposure and reduce, at least in theory, the number of potential victims a shooter might access. The more detailed and dynamic simulations introduce more stress and confusion and can be used to train not students and staff but first responders. No industry or national standards exist for the drills, and their design, goals and techniques vary widely, at times including simulated active shooters carrying mock weapons or firing blanks — an element that, like mass-shooting simulations themselves, has faced criticism for the risk of traumatizing participants, children in particular.

The Greenport drill was not imposed on the school’s staff or student body. It relied on students who volunteered to participate and was held on a weekend rather than during school hours. The village of Greenport worked with Firehouse Training Plus, a private firm that helps departments enhance skills via refresher training and simulations, to stage the enactment of this recurring contemporary American horror. The firm’s founder, Chip Bancroft, a retired fire chief, says that effective drills require intensive planning, collaboration and outreach so no one mistakes them for real and that whatever public misgivings surround simulations, demand for them from school districts and public-safety organizations is rising. His company, he says, has more requests for them on Long Island than he can fulfil.

In designing the drill, Bancroft and his peers recognized the baked-in limits of local first-response capacity. In many areas of the United States, a mass shooting can almost instantly overwhelm trauma-care resources. Exurban jurisdictions often have few ambulances, a relatively small number of first responders and few-to-no nearby emergency rooms, blood products or hospital beds. Greenport is fortunate to have a fire station with ambulance service a few blocks from the tan-brick school buildings that house public-school students from prekindergarten through 12th grade, and a hospital with an emergency room a little more than a mile away. But the firefighters are volunteers, the ambulance service has two vehicles and the emergency room could not be expected to handle 62 patients. Within minutes, a mass shooting could create more severely wounded victims than could be carried or treated by Greenport providers alone.

Moreover, mass shootings are almost always a surprise. Unlike other perils that can stretch emergency- response resources — extreme weather, an advancing wildfire, a pandemic — there is typically no warning that would allow supervisors to marshal staff or stockpile equipment and supplies in the days or hours before victims are harmed. Multiple first-response providers would rush nearly simultaneously to a shooting, and coordination can quickly break down. Bancroft and the participating departments hoped the exercise would identify weaknesses and lead to improvements ahead of any real-life event.

The scenario Bancroft developed assumed a young man had opened fire on students and faculty as they sat in bleachers for a pep rally beside the football field. It also assumed the shooter then ran into the school, where police officers were to contain and stop him. In the drill itself, there was no simulated shooting in the bleachers; the students who volunteered to act as victims did not see a mock attack. Instead, two exercises essentially played out in parallel. Outside, beside the sports field, the simulation’s victims took positions on and near the stands, and firefighters and emergency medical technicians rushed to treat and evacuate them. Inside, police officers practised confronting a man playing the part of the antagonist.

Even without a shooting being enacted, several participants said the drill had an unsettling feel, in part because Bancroft and other organizers outfitted the mock victims with fake gunshot wounds, doused them with artificial blood and assigned them roles to perform, including being in shock, emanating confusion or acting inconsolable, panicked or distraught. Four were assigned to pretend they were dead. To add stress and stretch resources further, smoke machines bellowed smoke in the nearby woods, a car was set afire and had to be extinguished and a medical-evacuation helicopter was summoned and landed beside the football field to simulate carrying critically wounded victims to Stony Brook University Hospital, roughly 50 miles away on roads often busy with traffic.

The volunteers, almost all of the high school students from Greenport or other districts in Suffolk County, gathered early to prepare. Among them was Diana Acevedo, 16, a junior at Bentwood High School who hopes to attend Columbia University and become a gastroenterologist. When organizers asked what role she would lie, Acevedo selected a bloody assignment. They affixed the latex likeness of a gunshot wound to her forehead and spattered her torso with fake blood. Thus adorned, and instructed to play dead, Acevedo spent much of the morning lying motionless on the grass. Though she knew it was a drill, she became uneasy as it began. The shots alarmed her. “One of my best friends, her name is Dayanna, she has really good acting skills and I heard her screaming: ‘Three of my friends are shot and no one is helping them! Please help them!’” Acevedo says. “When I heard these words I just imagined the little kids in Uvalde, Texas, shouting and seeing their friends dead. It hurt me deep inside.”

As first responders triaged the mock victims, one affixed a black tag to Acevedo, marking her as deceased and therefore a low priority for evacuation while rescuers worked on the living. Lying on her back in the sun, ants crawling over her arms, Acevedo heard her friend’s voice anew: “These are my friends! Why do they have black cards on their clothing?”

Her friend, Dayanna Roldan, also 16 and a junior at Brentwood, was notified of the exercise by the Brentwood Legion Ambulance service, where she and Acevedo are members of its first-responder mentorship program. At first, she was not interested. After the murders in Uvalde, she changed her mind. Roldan hopes to attend Stony Brook University and become an emergency-room nurse and felt a need for this type of training. “Unfortunately things like this happen,” she says, of mass shootings. “In order to prevent more casualties, you have to give a little more of your time.” When Roldan arrived at the field, she asked for a demanding role. “I volunteered to be hysterical,” she says, and so she spent the exercise shouting, running in bloodstained clothes through the crowds and even tugging and pulling on first responders, trying to drag them from treating the wounded to help the simulated dead. “I tried to make it as real as possible,” she says.

One firefighter, Second Assistant Chief Craig M. Johnson of the Greenport department, says performances like Roldan’s were disorienting. “The screaming, it hit us,” he says. “I had to backpedal just for a moment on that, to collect my thoughts, before proceeding. “The ominous feel fit the times. Just over a week later, a 15-year-old freshman at Greenport was arrested after threatening, the authorities said, to attack the school. The boy’s name was withheld to protect his privacy. After the arrest, the fire chiefs and Bancroft said their duties were ever more clear. “Our kids,” Bancroft said, “should have all the safety and protection we can afford.”

click to view the complete set of images in the archive

Guardians of the Zagros

© Emily Garthwaite

Guardians of the Zagros

© Emily Garthwaite

The Zagros mountains, in Western Iran, stretch for nearly 1,000 miles, from the sands of the Persian Gulf northwest along the modern border with Iraq and Turkey, separating the plains of Mesopotamia from the expanse of the Iranian plateau. Deep gorges and jagged peaks surpassing 14,000 feet buffered ancient empires from one another—Babylon in the Fertile Crescent and, to the east, the great metropolises of ancient Persia. They frustrated more than one invader, including Alexander the Great. But this forbidding mountain range is also rich in grasslands and rivers fed by winter snows, and for thousands of years, tribal groups have migrated through the Zagros with the seasons to pasture their goats and sheep. That gruelling, often dangerous feature of nomadic life has evolved, but it has not entirely disappeared. It persists to this day not only for practical reasons but also as a meaningful ritual for people whose history is rooted in the mountains.

Last October (2021), the Mokhtari family, members of the Bakhtiari tribe, prepared to set out from their summer encampment in Iran’s Isfahan Province. They were parents Hossein and Jahan, three of their nine children and several cousins and other relatives. Following timeworn paths through the Zagros, allotted by custom to their tribe and clan, they would travel with around five horses, ten donkeys and mules, and hundreds of goats and sheep. Their destination in Khuzestan Province was some 150 difficult miles away. The journey, known in Farsi and in the local Luri dialect as kuch, would take two weeks.

click to view the complete set of images in the archive

CAMO

© Thandiwe Muriu

CAMO

© Thandiwe Muriu

Inspired by the covers of prominent fashion magazines such as Vogue and the rich cultural history of her own Kenyan heritage, Thandiwe Muriu aims to highlight the natural beauty of women with whom she identifies. Muriu photographs her subjects in striking, intricately patterned fabrics that often resemble the traditional textiles of various African countries and cultures. Backdropping the subjects using the same vibrant pattern, Muriu creates hypnotizing illusions.

Muriu wants her models to both blend in and stand out at the same time. The images in her Camo - short for camouflage - series create an optical illusion where the person in the photograph almost disappears yet it is impossible to ignore her. "I love fashion photography, I could do that all day, but I realised it needs to be fashion photography that is a reflection of who I am and my background, that is how the Camo series came about."

The funky fabrics, elaborate hairstyles and improvised eyewear are an attractive and witty celebration of Muriu's culture. But there is also a critique. Muriu says the series is "a little bit of a personal reflection on how I felt I can disappear into the background of my culture.

"And my experience as a commercial female photographer was realising that very quickly - because of the cultural context - I can be dismissed and disappear." Muriu went into commercial photography, which in Kenya is male-dominated. "I'm small, I look very young and so oftentimes the biggest thing I would experience is people dismissing me. I would walk on to set and people would talk to my assistant who was male, assuming he was the photographer rather than me.

"I had to learn to be brave and bold and say: 'Hi, I'm in charge.'"

Looking at the images in the series it is obvious that constructing them is a meticulous process. It starts with choosing the fabric, which Muriu describes as one of the hardest but most enjoyable parts. Spending hours in Nairobi's fabric shops, she sifts through floor-to-ceiling piles of cloth imported from across the continent. She is looking for "something that's really loud with an almost psychedelic quality as if the fabrics are alive and moving and confusing the eye". It is recognisably African but not necessarily the traditional designs. "We're in this new Africa, this new generation, where we love our prints but we're not going to wear them in traditional ways." Another key stage is the hair. As the project developed, Muriu became more intentional about her exploration of African beauty. She researches historical and traditional hairstyles. Then with the help of a stylist gives them a "modern, funky twist but they are based on hair that our ancestors actually used to wear", she says.

"It became more than just looking at beauty. It was about asking: 'What are some of the symbols of beauty that we have lost?'"

The eyewear, made from soft drinks cans, plastic tea strainers, clothes pegs, bottle brushes and other objects represent the innovative way that many everyday things in Kenya are repurposed for other uses, Muriu says. They also add to the humour of the images which the photographer wants to make visually stimulating and enjoyable, while at the same time tackling some very profound issues.

click to view all the images in the series

Native Sovereignty

© Kiliii Yuyan

Native Sovereignty

© Kiliii Yuyan

For thousands of years, Vancouver Island, an island 1/3 the length of Canada’s Pacific coast, was the home of the Tla-o-qui-aht. They controlled who lived there and who was a citizen. Their laws dictated who could launch boats from the islands, who could cut down their conifers, who could fish for salmon and where. From the 18th century, European invaders sought to strip away that control. The Tla-o-qui-aht, resisted fiercely and constantly, for decades. By many important measures, they succeeded. Today, central Vancouver Island is again under Tla-o-qui-aht control.

More remarkable still, scores of other Native societies across North America are following in Tla-o-qui-aht footsteps. In legal terms, all of these groups have been, and continue to fight for the sovereignty promised to them in the hundreds of treaties the United States and Canada signed with their original inhabitants.

To Indigenous people, the word 'sovereignty' means more than self-rule. It is shorthand for a vision of Native societies as autonomous cultures, controlling the environment around them, part of the modern world but fully rooted in their own long-standing values, and working as equal partners with local, state, and federal governments.

All of this is happening now. From BC to Texas, Indigenous peoples are co-managing national forests, forcing governments to pull down huge dams, blocking pipelines, taking charge of fisheries, and rebuilding prairie ecosystems.

At the same time, Indigenous nations are rebuilding in all the other dimensions of sovereignty. Some have created billion-dollar businesses. Some have built alternative hospital networks and sports leagues. Some have reacquired large chunks of the land that was taken from them. All the while, Native artists and craftspeople have joined new technology and ancient values to create distinctive, entirely contemporary forms of architecture, painting, weaving, and writing.

extract by Charles C Mann

click to view the complete set of images in the archive

And then there were only two

text: Boštjan Videmšek, Maja Prijatelj Videmšek

photos: Matjaž Krivic

And then there were only two

text: Boštjan Videmšek, Maja Prijatelj Videmšek

photos: Matjaž Krivic

Future in the freezer!! How a species of rhinos can be saved in a test tube.

The northern white rhino is all but extinct. The two last males died several years ago. Two females are still with us, but too feeble to bear babies. In an Italian laboratory, their eggs are now artificially fertilised by sperm from the three late males, and kept at minus 196 celsius, in hope that surrogate rhinos from another subspecies can carry the northern white back from the brink.

click to view the complete set of images in the archive

Cesare Galli screwed off the lid of a liquid nitrogen canister and pulled out a sample labelled Fatu NWR x Suni NWR, 9. 4. 21. We were afforded a glimpse of an invaluable rarity: a pair of northern white-rhino embryos, created in March and April at the Avantea lab in Cremona.

Thus far, the Italian lab has managed to create fourteen embryos. The scientists allied with the BioRrescue consortium plan to use them to resurrect functionally extinct species. Only two female northern white rhinos are left: Fatu and Najin. They are unable to conceive in a natural manner.

Mr Galli is impatiently awaiting the arrival of the first northern white rhino baby in twenty-two years. »To the people asking when, I reply: 'In five years’ time...' I've been saying that for a couple of years,« explained the founder and manager of the Avantea biotech company specialising in advanced animal-reproduction technologies and research.

His company was invited to participate in the northern white rhino project on the strength of its two decades in elite-horse reproduction. In this field, Avantea's expertise is second to none, and horses are biologically the most closely related farm animals to rhinos. The Avantea lab was the first to artificially impregnate a mare, using an embryo created through the direct introduction of a sperm cell into the cytoplasm of an egg cell (ICSI technique). This is also currently the most widely used technique for artificially inseminating human beings.

Avantea's experts wasted no time in tailoring the horse-breeding protocol to the needs of rhino-embryo creation. Prior to that, Galli spent several years perfecting the method with the Sumatran and southern white rhinos, though he ultimately failed to produce an embryo. In 2018, he managed to fashion a hybrid embryo between a northern and southern white rhinoceros.

The fourteen northern white rhino embryos created by Avantea in 2019 are currently stored at minus 196 degrees Celsius. In all cases, the role of Eve was played by 21-year old Fatu, a female residing at the Ol Pejeta Conservancy in Kenya, and the role of Adam by two deceased males Suni and Angalifu. The egg cells of Fatu's mother, 32-year-old Najin (also located at Ol Pejeta), proved uncooperative with Avantea's embryo-creation procedures. Due to Najin's age, medical condition and welfare BioRescue team have recently decided to cease harvesting her unfertilised eggs (oocytes) following an ethical risk assessment in 2021.

Since neither Najin nor Fatu can bring them to fruition, the plan is to insert the embryos into southern white rhino surrogate mothers. And this could as much as Thomas Hildebrandt who heads the department of Reproduction Management at Leibniz-IZW institute is concerned, happen soon. “Hopefully, we could do the first embryo transfer in the coming months. All the involved parties have to agree on that, but I think that we have to use the momentum and proceed as soon as possible,” we were told by the German scientist, who has developed the embryo transfer technology and is a driving force of the whole project.

»One female and two males are not enough to foster a self-sustaining population,« Cesare Galli conceded. »But if we create four embryos per year, that makes sixteen in just four years. If we reach a 50-per cent success rate, as we already have with horses, we would have eight new animals. This won't be enough to repopulate the whole of Kenya, but it would be a good start.« ***» When you eliminate a species from the ecosystem, you risk throwing everything off-balance. Rhinos are maintaining the balance. They are also iconic species. And the danger to their survival comes exclusively from us. It is our duty to make amends. The southern white rhinos, for example, we're facing a similar situation. But after South Africa put them under special protection, their number soared to over 20,000. The northern white rhinos had the additional misfortune of all the wars raging in the middle of their natural habitats.« Galli was referring to parts of Uganda, Chad, Sudan, the Central African Republic, and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Happy Grazers

The planet's last two remaining northern white rhinos are kept behind three electrical fences and protected by a squad of rangers at the Ol Pejeta Conservancy in central Kenya. Up close, Fatu and Najin seem unperturbed by the wider implications of their species' imminent extinction. Their days follow a simple and uneventful routine. Their nights are spent in their snug straw-covered pens among a host of whistling thorns (Vachellia drepanolobium). From about six to nine, they can be found grazing along with their approximately 2.8-square kilometre enclosure. Once it gets too hot, they fill their bellies with water and lie down to rest, only to resume their grazing when it gets a bit cooler. They adore rain, impromptu mud baths and sharpening their horns on nearby trees.